Do the work

Confidence and simplicity is a harmful cocktail.

Dear readers,

I’ve been an avid user of data aggregators for as long as I’ve been investing. As my investing journey has developed, my focus on various metrics have changed.

In the start, I overfocused on share prices that had dropped a lot, great stories promising a future of plenty and potential for revenue growth as well as large, revolutionizing total addressable markets. Thankfully, I have been, and still are, learning a lot about various quantitative metrics that better tell the stories of great investments than hopes and dreams peddled by people looking for quick gains. EPS growth, FCF-yield, ROIC, reinvestment rates and so on.

This has been supercharged with my use of several data aggregtors. Today investors have any data they want at their fingertips. Sophisticated tools such as Finchat and FastGraphs. In moments you can look up historical numbers from accounts, and find the calculated metrics such as return on capital and so on.

I’m sure that if us small-timers have access to these sophisticated tools, the institutional investors have access to even better gadgets. As investors seek objectivity and rationality they lean more and more on numbers. After all, cash-flow is all that matters.

I love using these data aggregators. They often save me a ton of time, give plenty of insights and in Finchats case even allow for AI-assisted computing and data fetching. It’s an excellent way to get a quick overview of the underlying development of the economic scales of the organisations in which we hope to make money investing with.

However, as these tools get more and more sophisticated, and the metrics we can pull up at a moments notice continues to better, it puts investors in risk of narrowing our field of vision. And remember, at best we’re playing catch-up with the true forces in the market: The big time institutions. The paradox is: Better tools lead to higher confidence in their calculations and interpretations of the reality.

Everything is not as it seems

Data aggregators have several ways of collecting data. Most use some form of script or AI to find and collect the data. Numbers are compiled and computed through sets of formulas. In Finchats case, they are open about how they collect the data and which formulas they use to calculate the various metrics.

But it is important to remember that numbers ≠ reality. Accounting holds many nuances, and as an amateur I’m terrified any time I get a question in regards of accounting. There’s a reason people earn certificates of accounting. It’s a complex field, and understanding and interpretation of accounting is important to how you view finances of companies. Understanding what is being boiled down into essences is the key here.

With the entry of these available, efficient and rather precise data aggregators I find that we have entered into a paradigm of over-reliance on quantification. On top of that, quantitative investing has gained popularity as technology and computing has allowed sophisticated investors to encapsulate more and more data in models that make calculations for them. Model-based investing is a super interesting approach in my opinion, as it focuses on discipline, uniformity and comparability to create investable universes not based on the investor preferances, but on hard metrics. It is however not for me.

As the spread of quantified understanding of investing keeps gaining traction investors seem to congregate to a lot of the same conclusions. We tend to focus on the same ideas, watch the same sectors and follow the same rules. Not only is the field of vision narrowed, but the sieve in which we sift out ideas also becomes smaller.

But investing is not about doing what others do, it is about differentiating oneself from others in a positive way. Overreliance on screeners hamper this, because it creates a totally average (and at times faulty) understanding of the business.

Lately I’ve looked at a couple of companies that doesn’t screen well: Momentum Group AB, Berner Industrier and Fairfax Financial Holdings. The first two names have been through restructuring or spin-off processes, whilst the latter has had fluctuating performances historically with different approaches by the management. When we run these three names through screens, they seem quite underwhelming. Poor FCF development, share-price volatility, weird return on capital metrics that don’t look like anything like quality. But, pull off the covers, open the annual reports and start doing your own computing, and they seem like wildly different beasts.

Remember, AI and screeners are tools. They excel at what they're designed for: processing vast amounts of data and identifying patterns. They should serve as sophisticated assistants that help us ask better questions, not provide final answers. The real work, reading annual reports, understanding qualitative competitive advantages and what potential changes in the business that the market isn’t pricing right is what drives returns. That’s the work we have to do.

For instance, a screener might flag a company with declining FCF as uninvestable, but this same metric could indicate heavy growth investments that will yield future returns. The screen gives us the starting point; our analysis determines whether that declining FCF represents deterioration or opportunity.

The devil is in the detail

I want to quickly provide some examples:

Not all expenditure is created equal

If we own a business generating ROIIC between 20-30% and they’re expanding capacities, shouldn’t we be excited? If a company is spending more on salary when we know the salary to earnings ratio is somewhere between 60-70% on average, shouldn’t we be happy? But if a company is buying turn-around companies because they don’t know how to grow organically, some slight concern should pop up. Some expenditure is spent to grow, some is spent to maintain the business. We want more of the first, and less of the latter. We need to put in the work to understand how much and why some of capex is growth capex. A key question here is: How does this company’s reinvestments build future growth?

FCF is often very faulty

Cash-flow is king is a common saying amongst investors. But the metric FCF is commonly an after investments metric. Many companies are punished for their high reinvestment rates by investors too obsessed with free cash flow. Look at operational earnings instead.

Not all adjusted numbers are bullshit

Many companies like to post their own alternative metrics. Most do it to obscure, and paint a prettier picture than what exists. But some times, adjusting metrics makes sense. Take Schibsted: They’ve sold most of their businesses and discontinued a bunch as well. I find it reasonable to adjust so that we see steady state operational earnings. On the other hand. companies don’t adjust earnings when they should, for example earn-out revaluation should always be shown clearly by the reporting company as it often artificially boosts numbers.

Enter conversational and generative AI

As investors become increasingly reliant on quantitative metrics from data aggregators, we now face an even more powerful short-cut: conversational and generative AI. These technologies represent the next evolution of the same trend - offering convenience and efficiency, but potentially at the cost of original thinking. While data aggregators compile and calculate figures, AI systems like Perplexity and Claude go further by interpreting that data, synthesizing patterns, and even generating investment narratives. This creates both new opportunities and deeper challenges for those seeking differentiated returns.

But as these tools become more available and widespread, I think we are bound to further homogenize our understanding of the market. That does not help us as investors differntiate ourselves from others. Now, I want to say that I do not think being different in itself is important - as Howard Marks has mentioned several times: Being contrarian is not a great strategy in isolation - If everybody tells you jumping off a cliff is a bad idea, you probably shouldn’t be contrarian.

If you want differentiated results (i.e. other than the index which is the average) you need to do something different. And preferably something that differentiates you in a positive way (i.e. higher returns than the index).

What is it that generative AI chatbots does? Well, they aggregate data, and offer up the average of available information. So by leaning into AI in research and writing you make your understanding and information even more in line with the average. That’s no way to gain an edge. Use it, but use it as a interactive helper, not a fountain of truth.

Cultivate an edge: Read the reports

In the end, if you want to outperform and have differentiating returns: You need to have a differentiating view. Use screeners, AI and so on - But remember that without context, understanding of the actual businesses and what makes a potential good investment. For numbers to make sense, you have to understand the context that produces these numbers.

In the end, we need to attempt to falsify numbers - can it really be as good as the numbers tell us? What are the potential faults in the business, and will it keep being as good as it has been? Some great things to look into is working capital management, how they allocate capital between growth, shareholder returns and so on.

I’ve experienced people who’ve read my comment ask me how I find this much information on the company. Most of the times, I answer: I’ve read the annual report.

As our analytical tools improve, the harder it becomes to generate analytical edges. When everyone has access to the same sophisticated screeners and AI analysis, the edge shifts from information to robust processes and behavioural discipline. Here are some suggestions to how to better use these tools other than cut corners:

Use AI to test your hyptohesis and your understandings

Use screeners to get a breadth of understanding of many companies, not depth on a few

Always use primary sources, reports that have been written and verified by actual humans (that list their sources) and try to figure out things yourself

Have you ever heard any succesful investor say “Well, I have access to a lot of information online, so I find a lot of good cases”?

I think this talk from Li Liu touches on some interesting parts of investing. But the most important part is his clear message to the students: You have to do the work.

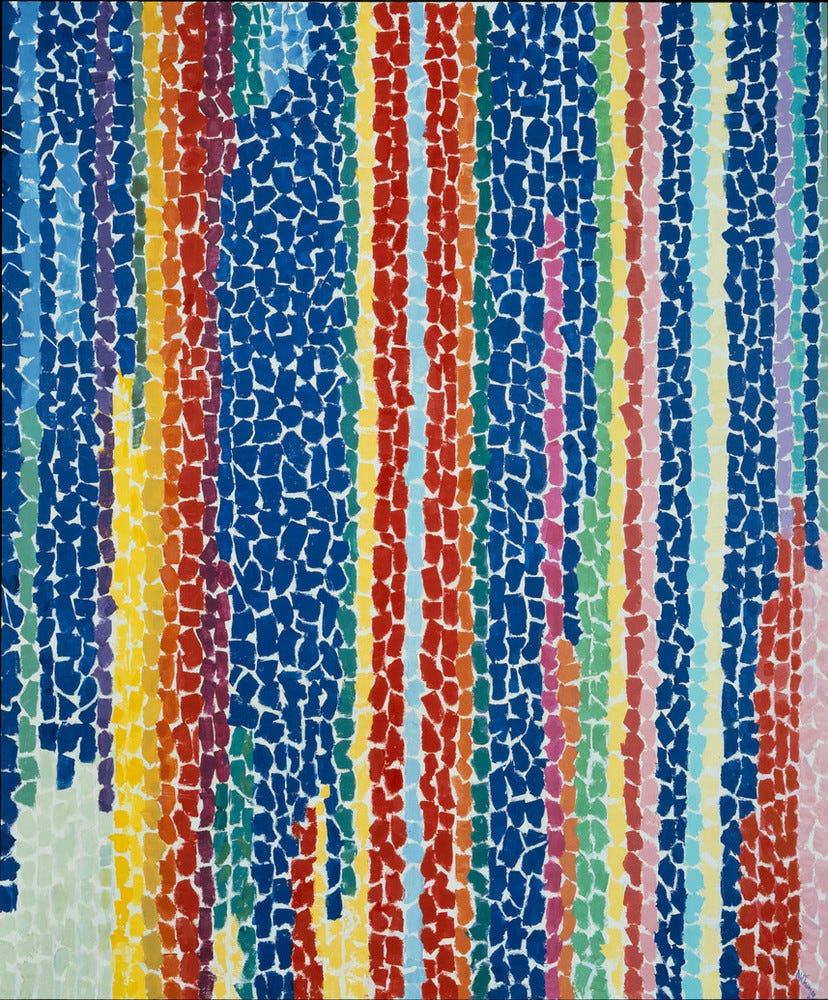

Thanks - enjoying your Substack (& am a Berner shareholder), but am also a Alma Thomas fan, so like the pic here!