Dear readers,

I often tend to see investors debate if stock X, or metric Y is the best way to understand investing. As investors, we have a tendency to define ourselves within categories, in which we hold strong beliefs of what is right and wrong. Based on this understanding, we define markets as bubbly, poor, great or straight out mad. A value investor is bound to complain throughout bull markets, a low volatility investor steers away from great companies because their share price fluctuates a lot.

Based on my own experience, the most long-winded discussions about investing I end up in, springs out of different positions (talk about knocking in an open door). But what I mean is that we’re talking about “rights and wrongs”, whilst having a completely different world-view of investing (or paradigms, to use fancy-speech). We’re simply playing different games. This brings me to one dimension of investing I’ve been mentally playing with lately: Understanding investing through the lens of games.

What is a game?

This idea popped out of the pages whilst reading the book “Finite and Infinite Games” by James Carse. It’s an excellent read, intended to talk about how to approach life through the lens of playing games. However, I feel many of the concepts discussed by Carse are applicable to investing.

Let’s first understand what a game is:

It’s a rules-bound activity.

It involves several participants.

It is either finite or infinite.

Usually when we talk about games, we view them as a competition between two or more participants. Games are often viewed as sports, but if we think about a game, it does not have to be a contest. Games are also always bound by a set of rules that the participants agree upon, such as the offside rule of football or the point system of golf. Most games last a set amount of time. Again, let’s look at football: 90 minutes divided into two 45-minute halves separated by a 15-minute pause. Whoever has the most goals at that time wins the game.

In the game of life, most finite games can last no longer than till death. It can be a career: You adhere to the workplace and workculture rules, and compete with other people to advance as far as possible in a career. The most skilled at balancing the written and unwritten rules of the workplace ends up with the best-paid or highest status job.

Carse also presents the idea of infinite games. These are games that never end, where the rules change and participants are unknown and changing. The goal of an infinite game is not to win but to keep playing.

The goal and rules of infinite games are defined internally by each participant, creating freedom to navigate the game as the participant wants it.

I think another very useful concept introduced by Carse is the distinction between how players in either infinite and finite games prepare for surprises. As the goal of a finite game is for it to end, the player in a finite game has to try to control the future so that he has the highest chance of achieving the desired outcome within the game. The player in a finite game works, exercises and prepares with the goal that he or she should be able to handle surprises. A surprise is an obstacle to overcome, not an addition to the game.

However for an infinite player, the goal is to make the game last as long as possible. Surprises and changes are the very foundation of an infinite game, and an infinite player’s goal is to ensure that surprises are seized and that they contribute to the game. Carse puts it in a way that I find useful:

To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.

Education discovers an increasing richness in the past, because it sees what is unfinished there. Training regards the past as finished and the future as to be finished. Education leads toward a continuing self-discovery; training leads toward a final self-definition. Training repeats a completed past in the future. Education continues an unfinished past into the future.

I find this approach very rewarding, and I think it plays well within investing: To train is to learn how to perform in a set way, in a set market. But as the future, and the world (which markets are a proxy of) is uncertain, surprises pop up. These can be the “black swans”, popularized through Nassim Talebs writing, the Covids and the Trump administrations “sudden” shift into what many perceive as a new world order.

If we continue to perceive the world as we have been trained to perceive it we are bound to fail at performing in a positively differentiating way. Embracing surprise will lead us to think “Well, this is a new situation, how can I, based on my given skillset, operate as well as I can within this new game?”. I think this is a more constructive approach than staying anchored to our trained perception of what the rules are and should be.

I will try not to leap too much into the field of philosophy, so I’ll leave it at this brief and inadequate introduction to the ideas presented by Carse. But for the continued discussion, I believe it is important to keep in mind some important concepts:

You can choose what sort of game you want to participate in.

Different games have different players with various goals.

Understanding the rules and the time horizon is essential to understanding a game.

These core concepts from Carse—game selection, rule structures, responses to surprise, and the distinction between training and education—provide a philosophical lens. But how does this abstract framework illuminate the concrete world of investment decision-making?

How can this be translated into investing?

While Carse's provides a philosophical foundation, its real power emerges when applied to the world of capital allocation. The stock market—with its mix of competing strategies, evolving rules, and diverse participants—represents perhaps the ultimate arena where both finite and infinite games unfold simultaneously.

Be mindful of who you play with

In investing, other participants usually have a lot to say for the outcome of your investment. Just think of the meme-frenzy of Gamestop or the hype that blew up in the faces of a lot of (well-motivated) green energy investors these last years. If you participate in sectors that are currently understood as the “next big thing” you usually participate alongside investors prone to overreaction and overoptimism. As history has shown us: The next big thing (NBT) never turn out how we think.

Playing the investing game alongside these investors exposes you to their fluctuating perception of the world. This player base is a fickle bunch. When investing in the NBT, fundamentals are not what’s important, but rather the story and potential. Understanding that the story matters more than the fundamentals such as growth in EPS, ROIC and margin stability is vital in the game of investing in NBT. But, with the caveat that fundamentals always catch up, and bring us back to earth again.

On the other hand, investing in companies that have been around forever, in consolidated sectors where you can clearly see who holds the position of top dog(s) allows you to participate alongside prudent players. These usually play for the long term, seeing that their investment might not shoot to the stars, but have good odds on reaching the treetops. And over time, these investors might have a better chance of achieving lift-off in portfolio levels.

I’m convinced that high absolute stock prices (I.e. the Berkshires, Constellations, AutoZones, Lotus’) are companies where you play with rational and fundamentally driven investors. The 19-year olds who want to get rich quickly, rarely have the bucks it takes to buy stocks in these companies.

Warren Buffet has addressed this several times:

"Splitting the stock would downgrade the quality of the shareholder population"

"The key to a rational stock price is rational shareholders, both current and prospective. Manic-depressive personalities produce manic-depressive valuations”

Shares with a high price can signal long-term minded management that don’t fall into the temptation to do stock splits to make their shares "accessible.” A company should not care about having an accessible share.

Howard Marks have often said that risk in the markets is in the end a result of people. It’s afterall people’s perception of the future that dictate whether shares will become priced beyond perfection, or into full depression. I’m convinced that as investors, we should be mindful of the sort of players we are entering into our game with.

Understanding the rules and who makes them

Another important part of the games is naturally the rules. These are usually there to define how to play the game, who can play the game, what decides the outcome of the game, and so on. Every game has rules that define the internal limitations of the game.

Don’t worry, I haven’t gotten so big on myself that I believe I know or can define the rules of investing. I doubt there are any universal rules defining how to best make money. But when picking the game that best suits you, try to understand the rules that follow.

Different approaches and investing styles naturally play within different rules. Let’s use the crude ideas of people being either value, quality or growth investors. What rules can we identify in this approach?

Value: Mind your multiples, price is what matters, quality is fleeting, and you win by identifying the biggest mispricing you can find.

Quality: The winners will keep on winning, it’s hard to put a price on quality, longevity matters, avoid debt, and you win by pitching in with the proven winners.

Growth: The future is now, profitability is secondary to growth, speed is good, disruption and uncertainty is a good thing, embrace debt, and we win through finding the next big thing.

Now, these are simplistic attempts at trying to identify some rules in various investing games. There are definitely a ton of nuances I am not touching on here.

Rules also depend on your approach to this game: Are you looking to play a finite game, i.e. one that you can see ending some time? Or are you in it for infinity? A lot of investors tend to say that the goal is to be eternal owners of businesses (popularized by Buffett again). But as Carse points out: Finite and infinite approaches should lead to different games and different rules.

In a finite game, rules stay as they have been. They have a clear structure, and boundaries. The rules define the game.

In an infinite game, rules change. They do not have a clear structure, and as there are no boundaries, they only exist as long as the player(s) want them to stay this way. The game defines the rules.

Understanding both your timeframe and the rules of the game you are playing, is important to be able to better approach investing. And remember, you can choose to play an infinite game in your investing, and navigate between many finite games. If you think value investing sounds smart, play that game as long as it suits you - but don’t tie yourself to the post when it turns out it’s not the game you want to play any more.

Playing an infinite game is more about playing so that you can keep on playing, and saying I want to do this forever, than being right on just how you play the game. Be adaptable, understand that change comes.

Morgan Housel put it well in his book “Same as ever”:

Long term is less about time horizon and more abut flexibility. The world changes, which makes changing your mind not just helpful, but crucial. But changing your mind is hard because fooling yourself into believing a falsehood is so much easier than admitting a mistake. Doing long-term thinking well requires identifying when you’re being patient vs just stubborn.

Dealing with and facing uncertainty

The rules that define investment games ultimately shape how participants respond to the market's most fundamental characteristic: uncertainty. This response reveals perhaps the most consequential distinction between finite and infinite investment approaches.

One thing that distinguishes great investors from good ones is how they approach uncertainty. In finite investment games, uncertainty is treated as a risk to be measured, controlled, and minimized. You'll see this in the obsession with volatility metrics, precise price targets, and complex hedging strategies.

Infinite investors, however, view uncertainty differently. They understand that markets, like life itself, are fundamentally unpredictable. Nick Sleep exemplifies this approach brilliantly. Sleep pursued what he called "scale economics shared" businesses—companies like Costco and Amazon that intentionally create uncertainty for competitors by continually reinvesting to lower prices for customers.

Sleep understood that certain forms of uncertainty can be advantageous when harnessed properly. In his investor letters at Nomad Investment Partnership, he emphasized that short-term unpredictability in earnings was often the very thing creating long-term competitive advantage. When the pandemic hit, companies following Sleep's model were already structured to adapt quickly, having built business models around continual evolution rather than stability.

This ties directly to Carse's concept of education versus training. Sleep emphazised the ability to recognize adaptable business models that could thrive amid constant change. The idea is to possess mental models flexible enough to respond creatively to whatever comes, viewing uncertainty not just as inevitable—but as the very soil from which exceptional returns grow.

Find the business models that not only have great moats, create tons of value and have a great product: But those that crank up their value to customers precisely when they need it the most, in times of volatility.

Freedom or limitations

The tension between freedom and limitation represents perhaps the most fundamental choice in how we play the investment game. Finite players establish clear boundaries to create certainty and control, while infinite players cultivate adaptability by embracing fewer constraints.

This distinction manifests directly in portfolio construction. Finite approaches establish explicit rules that must not be broken—specific valuation thresholds, sector limitations, or position size requirements. These rules define the boundaries of play and determine what 'winning' looks like.

Infinite approaches, by contrast, emphasize principles over rigid parameters. They establish a framework flexible enough to adapt as markets evolve, prioritizing continuation of the game over any specific outcome. The goal isn't to 'win' by a predetermined metric but to sustain participation through changing conditions.

I think what a lot of Carse’s text boils down to is whether or not to create freedom, or to impose limitations. This way of wording makes it sound like one is better than the other, but I don’t think it necessarily has to be like that. It’s about what you aim to do.

The investment landscape presents a fundamental dichotomy: create freedom or establish boundaries. This choice defines not just strategy, but one's relationship with capital allocation itself.

When examining structured investment approaches, we find deliberate constraints—a finite-game methodology with quantifiable parameters that establishes guardrails against cognitive biases. Structured investors typically:

Restrict investments to understandable businesses

Avoid unfamiliar sectors or technologies

Focus on specific valuation metrics (P/E ratios, FCF yields, ROIC thresholds)

Establish clear portfolio construction rules (position sizing, sector allocation)

This methodology has demonstrated remarkable resilience through market cycles. The structured approach prevents emotional decision-making—effectively limiting potential mistakes through predetermined rules.

Contrasting this, freedom-oriented investors embrace a more fluid methodology. Their frameworks provide minimal structure while maximizing adaptability:

Focus on fundamental business quality rather than specific metrics

Emphasize management quality and capital allocation

Identify sustainable competitive advantages and reinvestment opportunities

This approach allows investors to recognize similarities between seemingly disparate businesses when conventional metrics would exclude them. I think this is an approach that allows investors to focus on soft factors, in which you can approach investing pragmatically and be flexible in terms of what to invest in and not.

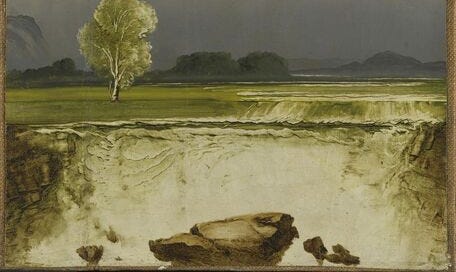

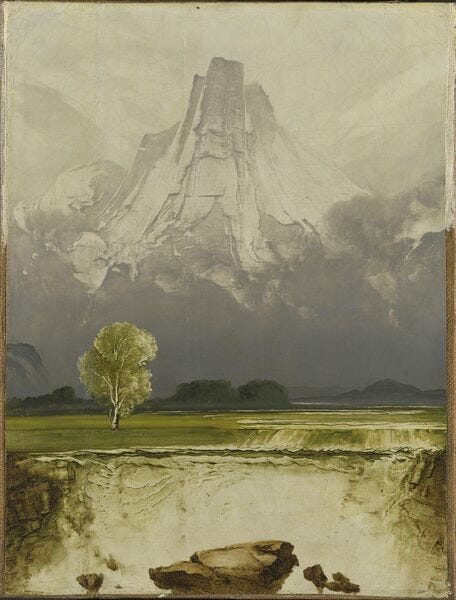

Machines or gardens

Another interesting concept that Carse puts out in his writings is the distinction between machines and gardens. This is a framework I find helpful in terms of portfolios. Do you want to operate a machine (rule bound) or mend a garden (freedom-oriented)

Machine constructions:

Portfolio as mechanism requiring optimization

Investor becomes extension of models and spreadsheets

Seeks to reduce variability through control mechanisms

Prioritizes historical patterns and established metrics

Attempts to minimize downside through classification

In the end, this way of building a portfolio is definitely a valid way. It’s not for me, but I know several investors who’ve achieved great results through rule-based investing.

Garden approach:

Portfolio as organic system with internal growth dynamics

Investor as cultivator rather than engineer

Embraces variability and unexpected development

Allows strongest performers to compound naturally

I find this approach to fit me better. It’s about organically figuring out what works for you, what fits in your portfolio and what companies you want to own. Some holdings will grow and sprout to heights, others will yield slow and steady results and some times you’ve got to weed out something that isn’t growing as you’d like it to.

The tension between freedom and limitation ultimately reflects our relationship with uncertainty. Both approaches have produced extraordinary results when executed with consistency and temperamental alignment.

There’s no right or wrong

This has been a bit of a waxing piece. I found Carse’s writing to be very interesting in terms of approaching investing. It’s naturally a bit of a philosophical piece, that might not match everyone’s preferences of reading, but I highly recommend it.

What I take away from the piece is that to be invested over very long periods of time is all about playing the infinite game. Don’t strive to achieve full understanding of everything, or define things in hard set modes. Rather, work towards education rather than training.

Training, according to Carse, is focused on repetition and standardization. It "regards the past as finished and the future as to be finished." A trained person learns established patterns and procedures for responding to anticipated situations. Training aims to eliminate surprise by preparing specific responses to known challenges.

Education, in contrast, "discovers an increasing richness in the past, because it sees what is unfinished there." It prepares a person not for specific scenarios but for adaptation itself. Education cultivates the capacity to respond creatively to the unexpected.

Because as we all know: None of us have functioning crystal balls or time machines. We have to embrace the changes that are bound to come, both in markets and our lives.